*Note: this essay was originally submitted for a university assessment as part of a Renaissance Literature module. Its original full length title is ‘Peace Over Liberty: Silence, Surveillance & Censorship as Mechanisms of Panoptic Disciplinary Control in Utopia.’ As always, I’d change a few things in restrospect; more specific and deeper use of theory & historical research, specificity of terms (i.e. ‘proto-communist’ over ‘communist’), cut down the insane intro (also nonsensical/paradoxical/contradictory conclusion) & my bibliographies are never, ever up to technical standards. But enjoy for now!

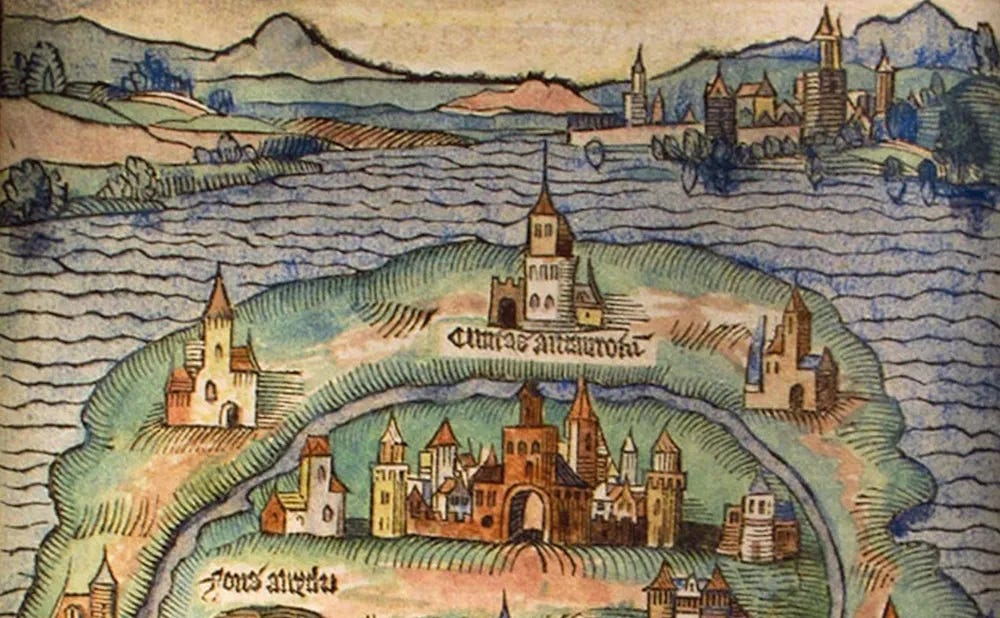

Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ (1516) sketches a portrait of an idealised communist society which envisions an end to exploitation by stripping away private ownership and despotic leadership. This vision not only reflects the humanist aspirations held by Renaissance political thinkers towards civic virtue - the realisation of one’s full potential for both their own good and for the collective good of the society in which they live - but also the tense contemporary debate which attempted to reconcile personal autonomy with the need for civic order. Quentin Skinner traces the humanist movement throughout the Renaissance in Italy, in its fraught search for a lasting political system that could provide peace and justice while maintaining liberty. He emphasises the humanist belief that “the maintenance of liberty in a Republic is best guaranteed by the promotion of virtù [civic virtue] in the whole body of its citizens” (Skinner, 175). Thus contextualised, the humanist question central to Utopia presents itself. How is it possible to instill civic virtue in each citizen so that they maintain the Utopian communist order of their own free will, without infringing on their liberty? I propose that Utopia does not venerate this society as an ideal, as it appears to do, but meticulously critiques Utopian methods of enforcing social harmony. Michel Foucault argues in ‘The Archaeology of Knowledge’ that spaces, groups and institutions have power, through a shared silence or discourse, to either suppress or form ‘objects’ (of knowledge), and to define and legitimise these – power over what is and is not knowable. While Utopia ostensibly promotes rational discourse, subtle mechanisms of silence, surveillance and censorship are utilised in order to delineate the boundaries of acceptable discourse and the objects formed as a result. Stanley Fish theorizes the concept of ‘interpretive communities’ – groups “made up of those who share interpretive strategies not for reading (in the conventional sense) but for writing texts, for constituting their properties and assigning their intentions” (Fish, 171). Censorship does not merely influence what objects are formed in Utopian public discourse, but how Utopians understand and interpret existing objects as an ‘interpretive community.’ The operation of Utopians as a singular entity with a rigid, uniform set of permissible beliefs normalises judgement, allowing for a disciplinary system of ‘micro-penality’, as put forth in Foucault’s ‘Discipline and Punish’, whereby slight departures from the ‘correct behaviour’ of the group are punished. Other systems of control and surveillance explored in Foucault’s work, such as the Panopticon, can be applied to Utopia, where nothing is private. Against the backdrop of the humanist struggle to establish a fair and ethical political system in the Renaissance era, Utopia reveals an inherent tension between the ideal of free dialogue and the practical necessity of limiting knowledge to maintain order, positioning More’s work as a nuanced critique of its own ideals.

Utopian mechanisms of silence operate subtly through laws and customs which emphasise social harmony and communal responsibility over individual freedom. Customs such as communal meals and volunteering to nurse a child are designed to cultivate a sense of community and mutual respect. While these conventions promote civic virtue, an implication pervades the text that a lack of participation in these common practices is a transgression that will be punished; either by law through slavery or exile, or more implicit punishment, such as shame and social exclusion. For example, “while it is not forbidden to eat at home, no man does it willingly because it is not thought proper” (More, 58). Not only is self-isolation from communal traditions discouraged, but active and willing participation is heavily encouraged and rewarded. When a mother is unfit to nurse her child, “any woman who can volunteers gladly for the job, since everyone applauds her kindness” (More, 58). With this dual mechanism of reward and punishment in place, one could argue that Utopian social harmony runs on a perverted kind of civic virtue. This ‘virtue’ does necessarily rely on moral education to be its citizens’ guiding light - the “instruction in [...] pure morals [and] principles useful to the community” Utopians receive while they are still “young and tender” (More, 102) - but instead on a carrot-and-stick system of moral guidance which functions to silence dissenters.

One may imagine that the citizens of Utopia, living in an ostensibly free and educated society, could seek out like minded individuals to discuss concerns and enact change, privately and without fear of persecution. On this point it is important to consider the structure of Utopia - distinctly separate cities and areas of countryside - and the legal limitations on mobility. This is similarly intended for collective social benefit; travel and population size per area is limited to allow an adequate workforce which shares labour equally among citizens. However, the limitations on and monitoring of citizen’s journeys - “They travel in groups, taking a letter from the prince granting leave to travel and fixing a day of return” (More, 60) - governs speech and behaviour in such a way that subtly discourages productive discourse. If one cannot travel alone, no singular dissenter may meet his peers to discuss reform without surveillance. Moreover, no Utopian space exists in which Utopians may speak freely without being heard. “The doors [...] open easily and swing shut automatically - and so there is nothing private or exclusive” (More, 47). The covert manipulation of Utopians into silence and conformity can be understood through the framework of Foucault’s theory of the formation of ‘objects.’ Every Utopian space, from the houses to dining halls, is public and communal, governed by Utopian laws and customs. Speech is regulated by one’s peers, which reduces potential ‘surfaces of emergence.’ These Foucault defines as the “fields of initial differentiation [in which] discourse finds a way of limiting its domain, of defining what it is talking about [...] and therefore making it manifest, nameable, describable” (Foucault, 41). With no safe spaces (surfaces) to discuss (discourse) alternative systems or ideas (objects), objects can never be formed. Utopians remain silent and think not individually, but as one.

Rooted even more deeply in the functioning of Utopia is censorship, as an essential element of social harmony, so citizens possess neither the capability nor the desire to question its political system. I have categorised this censorship firstly, as a lack of access to education, secondly, as the prohibition of beliefs that threaten the social order. Utopia’s utmost priority is to ensure that all those who are able, put in their fair share of labour to provide the country with necessities. However, this frequently comes at the cost of higher education. It appears that only a basic education is required and “not many people are excused from labour and assigned to scholarship full time” (More, 65-6). Even for these few, it is “only on the recommendation of the priests and through a secret vote of the sygrophants. If any of these scholars disappoints their hopes, he becomes a workman again” (More, 53). Hythloday observes that the Utopians are “far from matching the inventions of our modern logicians [or] being able to speculate on ‘second intentions’ [abstract concepts]” (More, 66). This being the result of Utopia’s educational practices strengthens the argument that Utopian leadership discourages the education of its citizens to quell discourses among them which might produce objects of knowledge conducive to political reform. The discouragement of education is linked to the encouragement of labour; another dual disciplinary system of punishment and reward. “Such persons [who do not care for the intellectual life] are commended as specially useful to the commonwealth” (More, 51).

Within Utopia, More notes that “Some worship as a god the sun, others the moon, still others one of the planets” (More, 95). This religious freedom plays a role in upholding Utopia’s appearance as a tolerant society whose citizens possess personal autonomy. However when Hytholoday relates that a Utopian man, exposed to Christianity, expressed his belief in the superiority of his new religion and “condemned all others as profane” (More, 97), it is revealed that this religious tolerance is not without parameters. He was subsequently arrested and “tried on a charge [...] of creating a public disorder, convicted and sentenced to exile” (More, 97). Here Foucault’s ‘enunciative modalities’ are being regulated as a form of censorship - his freedom of speech is restricted. Foucault’s ‘institutional contexts’ (rules governing where and how statements are made) appear in this case as the law, governing such statements by making an example out of dissenters using severe punishment. Like many of Utopia’s principles, this rule is intended for the greater good - so that religious conflicts do not compromise the peace - yet it raises the question of whether true liberation can occur concomitantly with true social harmony, if individual freedom of expression must be sacrificed to ensure it. Skinner notes that this was a major conversation between Renaissance humanists - a group Thomas More counted himself among (Kristeller) - who devoted themselves to “examining the machinery of government, asking themselves what role is played by laws and institutions in relation to the preservation of freedom” (Skinner, 171). The role of censorship in this scenario reflects Renaissance concerns about the destabilising effects of unregulated knowledge. An influence from an external society has been identified as a threat to Utopia’s carefully balanced social order, for introducing a belief system that may be considered superior to pre-existing ones, and is swiftly removed. Utopia has evidently chosen to prioritise peace, even if it comes at the cost of its citizens' knowledge of alternative ideas and systems. Towards the end of his chapter on the survival of Republican values, Skinner offers an explanation as to why a society may choose to enforce discipline rather than rely solely on civic virtue, supported by the views of political thinkers in Renaissance Italy, many of whom were ultimately disillusioned by humanity’s tendency to prioritise personal gain over the greater good. He asserts that Machiavelli’s ‘Discourses’ is “predicated on the assumption that ‘in constituting and legislating for a commonwealth it must [...] be taken for granted that all men are wicked and that they will always give vent to the malignity that is in their minds when opportunity offers” (Machiavelli quoted in Skinner, 186). Skinner thus concludes on the pessimistic note – “The entire age stands condemned as one in which virtù can scarcely be recognised, and even when recognised can no longer be pursued” (Skinner, 189).

Having established Utopia’s use of control to enforce harmony, it is essential to elaborate how these methods shape the society’s outlook as a whole, creating a self-perpetuating cycle which advances Utopia’s isolation from the world. The existence of a limit to permissible knowledge, in the form of restricted access to external societies and the treatment of knowledge as a communal resource, limits individual intellectual pursuits, promoting uniformity of belief. Describing the system by which Utopia supplies magistrates for neighbouring countries, More states that they are “strangers to the affairs of the city over which they rule” so that the “two evils, greed and faction” do not “take root in men’s minds” and “destroy all justice” (More, 85-6). Here More presents Utopia’s social order as a delicate balance that requires strictly controlled engagement with the outside world. As the censorship of religious beliefs has shown, the social order has the potential to quickly deteriorate with enough external influence; suggesting Utopia’s ideals are not universally applicable. This highlights the pessimistic view of the later humanists; that individual citizens cannot be trusted to act with civic virtue in the long term, and must to some extent be disciplined into acting for the collective good, for it is in human nature to be selfish. The language More uses throughout his descriptions of Utopian attitudes and customs is notable as it conveys the uniformity of a group whose individual intellectual pursuits have been restricted. More, speaking through Hythloday, consistently characterises the Utopians as a collective; of one mind, one belief system, one pattern of behaviour - “the Utopians think” (More, 52), “they consider” (More, 100). At every turn, the beliefs of one citizen are indistinguishable from another. Stanley Fish defines ‘interpretive communities’ as groups who share ‘interpretive strategies,’ encouraging the conception of the ‘self’ “not as an independent entity but as a social construct whose operations are delimited by the systems of intelligibility that inform it” (Fish, 335). Those who share a cultural milieu share a perspective, based on an understanding of everything they know. More’s construction of the Utopians as one ‘interpretive community’ stresses that limiting access to external perspectives and placing boundaries on permissible knowledge creates a narrow, inward-focused society resistant to change, who are easier to covertly control.

Utopia’s more apparent references to disciplinary mechanisms such as surveillance - “there are no wine-bars, or ale-houses; no chances for corruption; no hiding places; no spots for secret meetings” (More, 60) - are reflective of the apparatus Foucault describes in Discipline and Punish, suggesting an overt critique of Utopia’s systems. The Panopticon, a prison design that allows for constant surveillance (like Utopia’s communal living spaces) exercises a mental rather than physical constraint over its captives. “He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself” (Foucault, 202-3). Punishment in the form of slavery is an ever-present threat in the same manner as the ever-present threat of surveillance, constantly reminding citizens of the dangers of failing to adhere to the Utopian regime. “Slaves [...] are permanent and visible reminders that crime does not pay” (More, 83). By including some conspicuous forms of control alongside subtle manipulation into civic virtue, More embeds a nuanced critique of censorship and surveillance by leaving the desirability of Utopia unresolved. The dialogic structure of Utopia provides an interplay between voices which serves it well as a complex critique and a reflection on the debates of More’s contemporaries. More positions Hythloday as the admirer of Utopia and voice of idealism, so we may acknowledge its positive aspects and admire its aspirations towards civic virtue. Most compellingly, Hythloday’s name is derived from the Greek hythlos, meaning nonsense (Wilson) and utopia translates as no place (OED). More, in establishing Hythloday as a man speaking nonsense about a place that does not exist, makes his position clear: Utopia is the stuff of fantasy, it cannot apply in the real world. In contrast, More acts as the voice of pragmatism, his critical stance suggesting that while Utopia offers a compelling vision, its feasibility and desirability are uncertain, due to the suppression of liberty it requires, revealing weaknesses in the ideal of civic virtue when faced with the inherent flaws of human nature.

I introduced this essay with the Renaissance humanist struggle: is it possible to reconcile liberty and social harmony? Can a true Utopia exist, which operates on civic virtue alone? My arguments point to More’s conclusion being cohesive with the later humanists, and contending the idealistic early humanist view: a Utopia without compromise is simply impossible. Utopia thus critiques oppressive methods of control implemented in the name of social harmony, warning against placing too much faith in the good will of humanity.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

More, Thomas, et al. Utopia. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Secondary Sources

Stanley Fish. Is There a Text in This Class?: The Authority of Interpretive Communities. “Interpreting the Variorum” & “How To Recognize A Poem When You See One” Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Press, 1980.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. “Part Three, Discipline” New York, Vintage Books, 1975.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. “The formation of objects” & “The formation of enunciative modalities” New York, Pantheon Books, 1972.

Kristeller, Paul Oskar. “Thomas More as a Renaissance Humanist.” Moreana, vol. 17 (Number 65-6, no. 1-2, June 1980, pp. 5–22, https://doi.org/10.3366/more.1980.17.1-2.3.

Skinner, Quentin. The Foundations of Modern Political Thought. “The survival of Republican values” Cambridge ; New York, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

“Utopia, N. Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary.” Oed.com, 2023, www.oed.com/dictionary/utopia_n?tab=meaning_and_use#16046005, https://doi.org/10.1093//OED//7153815023.

Wilson N. “THE NAME HYTHLODAEUS.” Moreana, vol. 29, no. 110, 1992, pp. 33–34, www.proquest.com/docview/1321937140?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals.